Insurance coverage gains associated with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have stalled, and affordability and out-of-pocket costs are worsening.

45

Coverage gains stalled in almost all states since 2016

Health insurance in the United States is built around employment, and most Americans under age 65 (around 159 million people) get their insurance through their own job or the job of a family member.4

The ACA’s subsidized coverage expansions were designed to fill the gap for people without access to employer health plans, including those who lose their benefits because of job loss. The economic collapse triggered by the coronavirus pandemic is the first recession in which these provisions have been in place to stem job-related coverage losses.

Below we describe the state of coverage before the pandemic, what is known about the number of people who lost employer coverage in the downturn, and the degree to which people found insurance through the ACA’s expansions.

Trends in coverage and access

Federal data indicate more than 30 million people were uninsured in 2018, about 30 million fewer than the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) had predicted prior to the ACA’s major coverage reforms.5

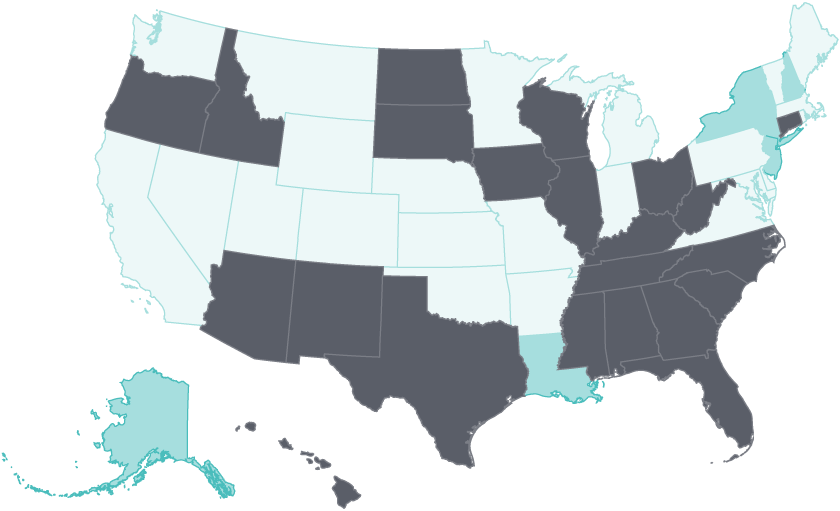

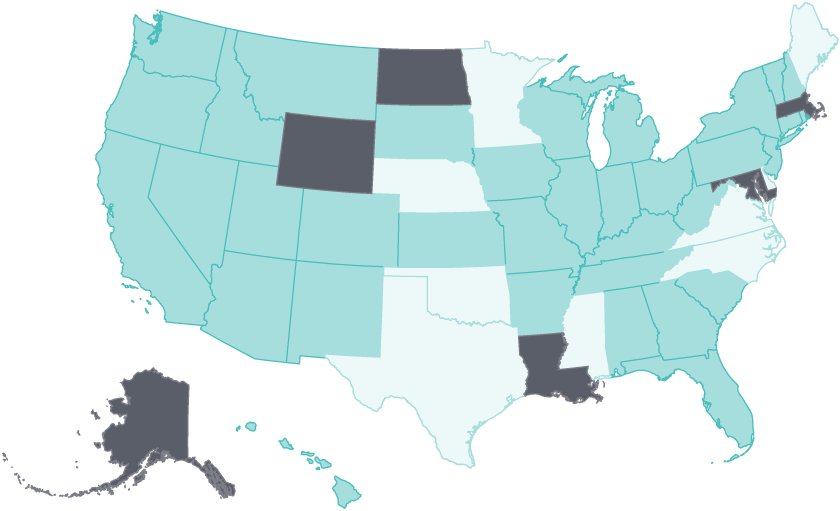

The biggest post-ACA coverage gains in all states occurred between 2014 and 2016. After 2016, gains stalled in 23 states and even began to erode in 22 states. The five states whose uninsured rates fell after 2016 had all expanded Medicaid eligibility; they include Alaska and Louisiana, which expanded Medicaid in 2015 and 2016, respectively.

The primary purpose of health insurance is to enable timely access to health care through the reduction of cost barriers. In most states, access improvements post-ACA enactment followed a pattern similar to what was seen for insurance coverage. The share of adults who reported going without care because of cost declined in a majority of states between 2014 and 2016. But after 2016, adults in 21 states experienced little or no improvement on this access measure, and 15 states saw a rise in the share of adults going without care because of cost.

Early gains in coverage and access following ACA expansion have stalled, and even begun to erode since 2016

- Select year ranges to see changes over time.

Uninsured adults

2014 to 2016 Adults who went without care because of costs

2014 to 2016

- Improving

- No Change

- Worsening

Notes: Uninsured rates are for nonelderly adults ages 19–64. Cost barriers to care are for adults age 18 and older. 'Improving' means uninsured rate fell by 2% or more per year OR adults with cost barriers fell by 2% or more per year; 'No change' means a less than 2% per year change in either measure; 'Worsening' means uninsured rate rose by 2% or more per year OR adults with cost barriers rose by 2% or more per year.

Data: Uninsured rates: U.S. Census Bureau, 2014–2018 One-Year American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS PUMS). Cost Barriers: 2014–2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

Share

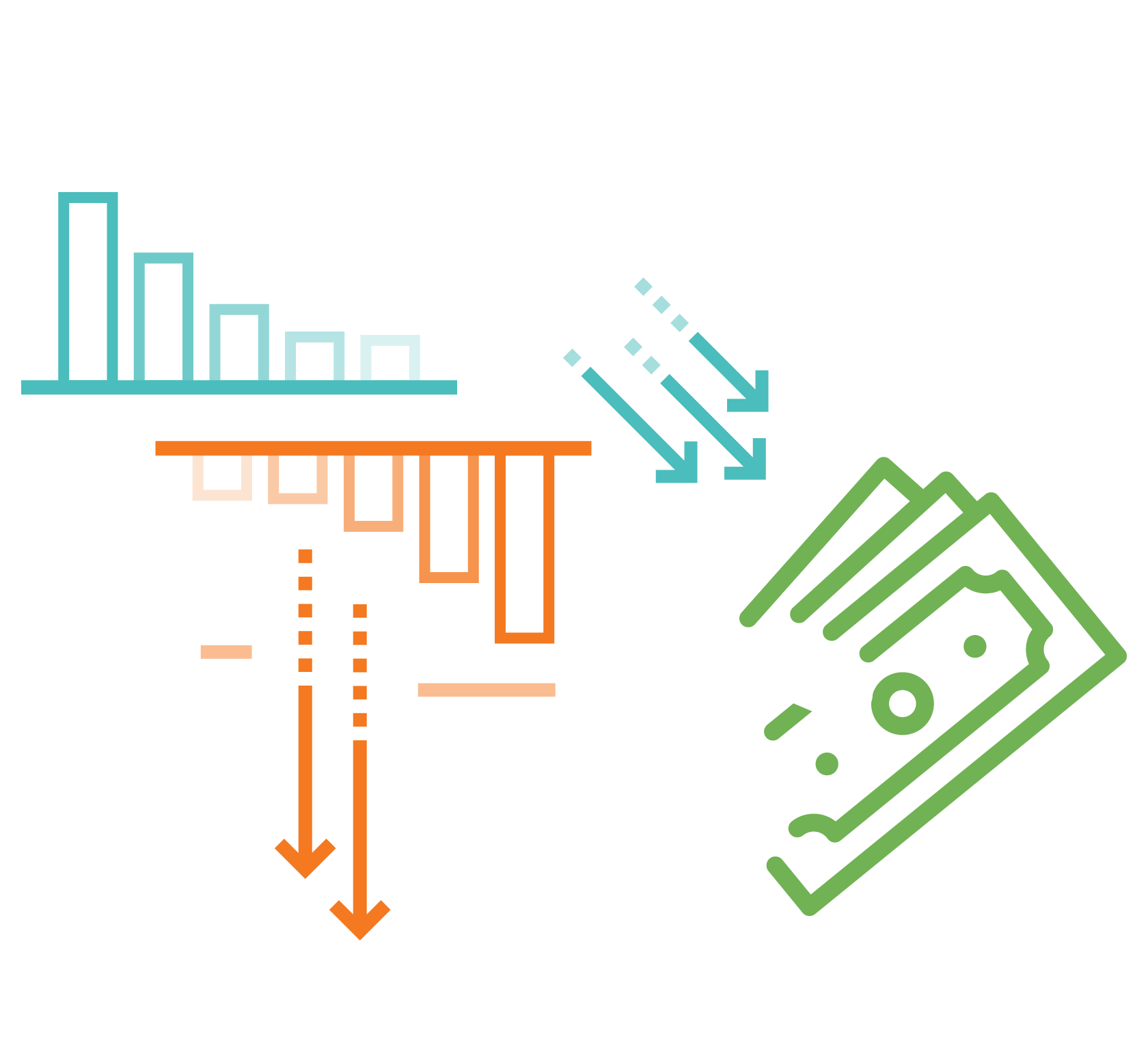

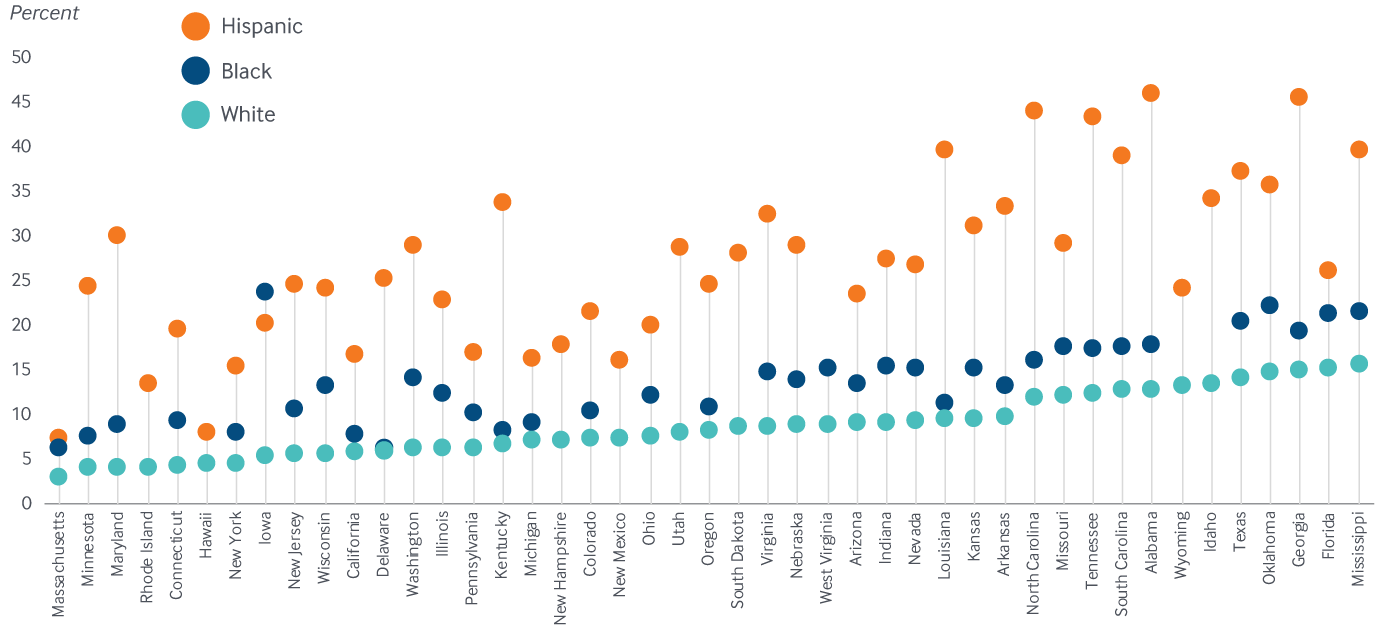

Racial and ethnic inequities in coverage persist and are at risk of worsening

Before the ACA, the uninsured were disproportionately people with low and moderate incomes and people of color. Research has found that the coverage expansions significantly narrowed both income and racial and ethnic inequities in coverage and access.6

However, these improvements largely stalled in most states after 2016. In 2018, the uninsured rate for both Black and Latino adults was at least five percentage points higher than it was for white adults in 17 states.

Four principal factors have driven the stalled gains and coverage erosion after 2016:

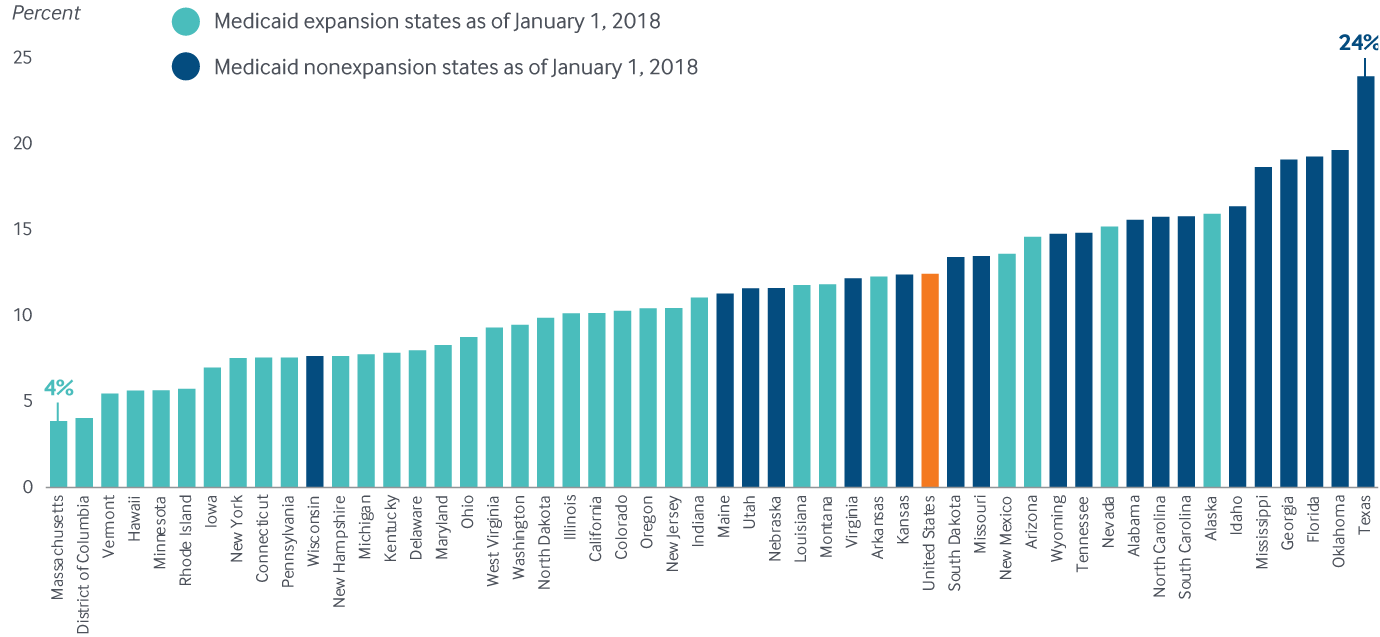

- Twelve states have yet to expand eligibility for Medicaid; uninsured rates in those states were among the highest in 2018.

- In the individual market, premiums become less affordable as income rises, particularly over the subsidy threshold of 400 percent of the federal poverty level ($49,960 for an individual and $103,000 for a family of four in 2020) where people pay the full premium.

- Actions by Congress and the Trump administration related to the individual market and Medicaid programs, along with immigration policies, have reduced enrollment

- Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for subsidized coverage under the ACA.

In 17 states, there was at least a five-point disparity in the adult uninsured rate between white and both Black and Hispanic adults

Notes: States arranged in order of the uninsured rate for white adults. Nonelderly adults ages 19–64. Alaska, Montana, Maine, North Dakota, Vermont, and the District of Columbia do not have sufficient sample size for at least two races or ethnicities. Rhode Island, Hawaii, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Utah, South Dakota, West Virginia, Wyoming and Idaho do not have sufficient sample size for one race or ethnicity.

Data: U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 One-Year American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS PUMS).

Share

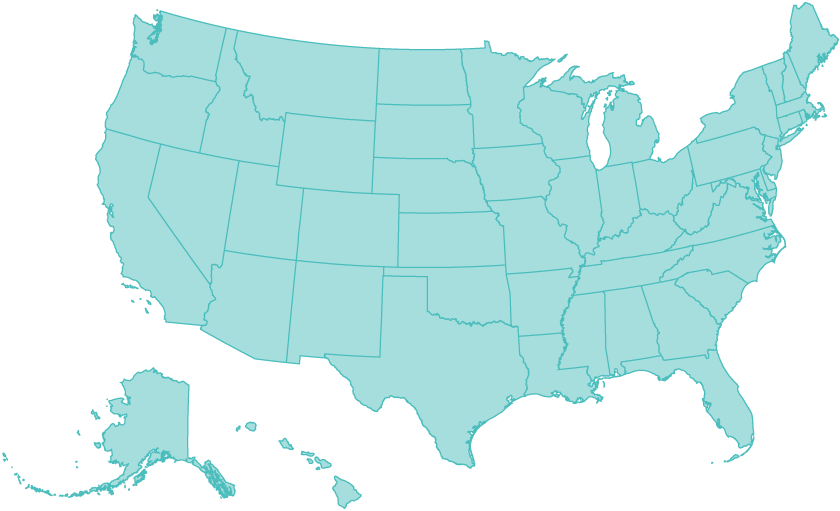

Four of the 12 states that have yet to expand Medicaid had among the highest adult uninsured rates in 2018

Notes: Maine, Virginia, Utah, and Idaho implemented Medicaid expansion after January 1, 2018. Missouri, Nebraska, and Oklahoma have passed but have not yet implemented. Nonelderly adults ages 19–64.

Data: U.S. Census Bureau, 2018 One-Year American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS PUMS).

Share

Implications of the pandemic for health insurance coverage

More than 50 million people have lost jobs or been furloughed since March.7

By August, the national unemployment rate was 8.4 percent; and as of July, Massachusetts, New York, and Nevada had the highest unemployment rates.8A Commonwealth Fund survey conducted in May 2020 found that about 40 percent of respondents, or their spouses or partners, who experienced job dislocation had coverage through an affected job, and one in five of those affected reported being uninsured.9 Because many of the affected jobs were in industries that often do not provide insurance, many respondents (three in 10) were uninsured prior to the pandemic. Black and Latino adults have been more likely to lose jobs during the pandemic, but almost half of Black adults and one-third of Latino adults live in states that have not yet expanded Medicaid, leaving them at high risk of staying or becoming uninsured. As of September 2020, more than 35 million people in the United States are estimated to be uninsured.10 The question is how many people who have lost job-based coverage will enroll in marketplace plans during the open enrollment period that begins on November 1.