Premature deaths from treatable conditions and deaths from suicide, alcohol, and drug overdose continue to impact life expectancy.

2x

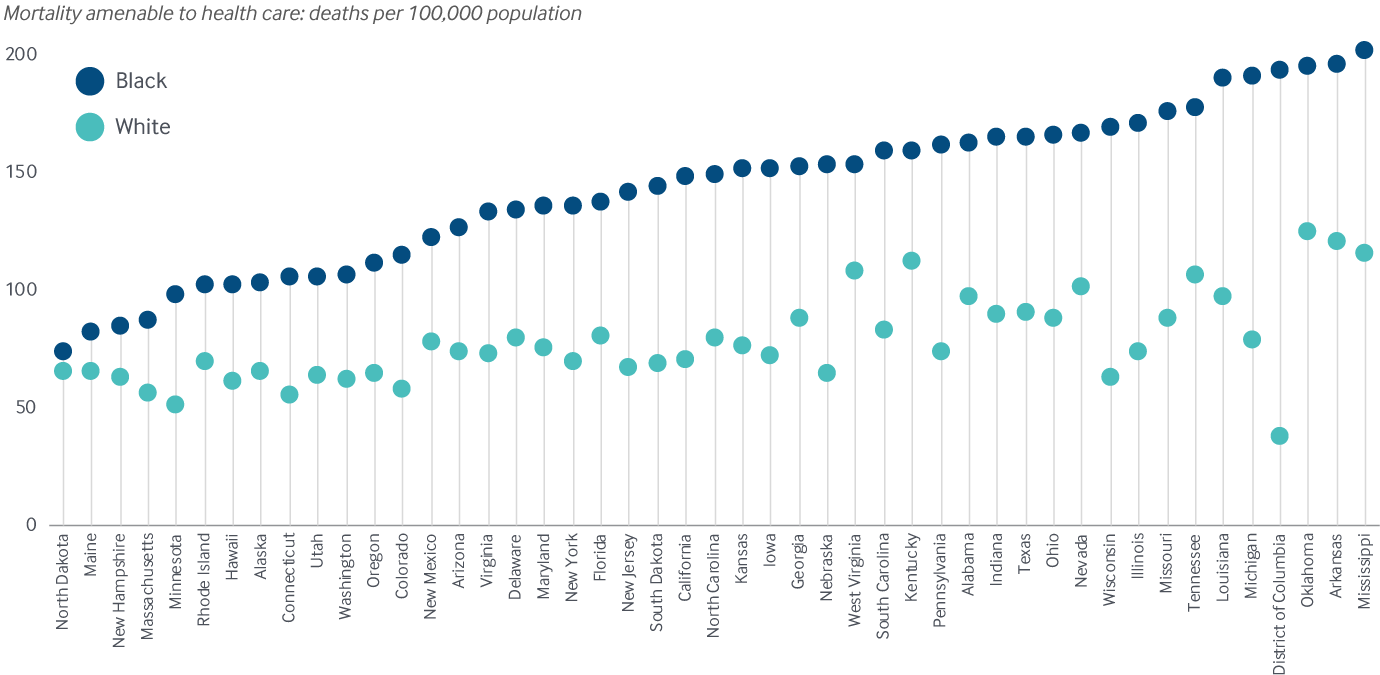

Blacks are twice as likely as whites to die early from treatable medical conditions

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a public health and economic crisis at a time when American health outcomes were already moving in the wrong direction. Decades long gains in life expectancy reversed after 2014, and adults of all races and ethnicities have been dying at increased rates.19 These trends are likely to continue in the wake of more than 185,000 COVID-19 deaths, and they may be exacerbated by the deep decline in the use of health care services unrelated to the disease and the greatest increase in unemployment since the Great Depression.

Deaths from suicide, alcohol, and drug overdose

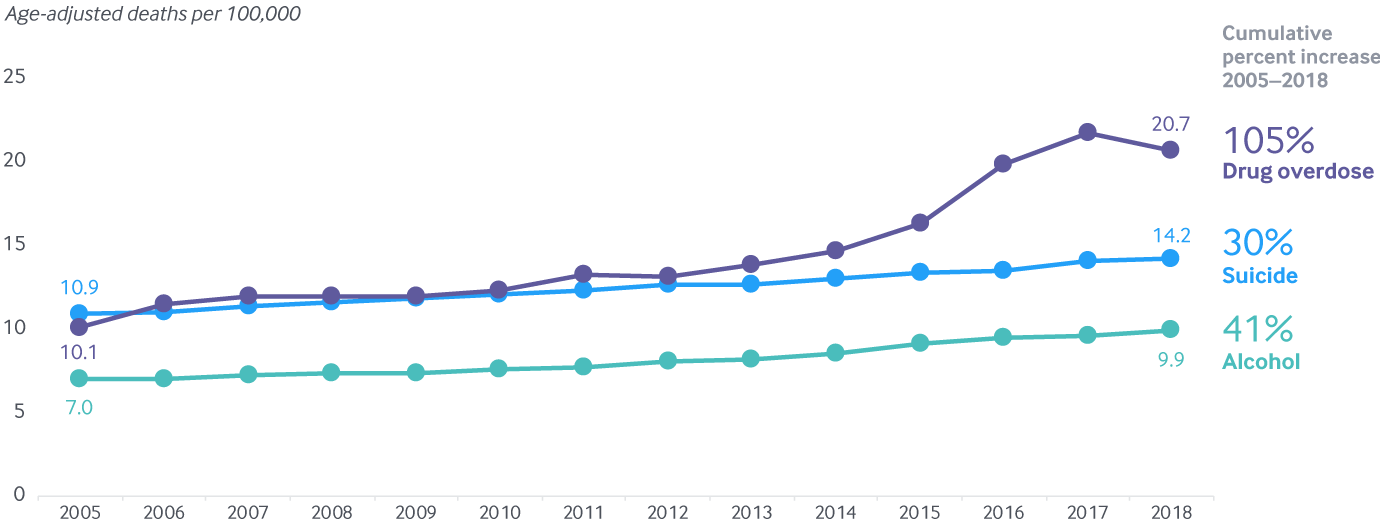

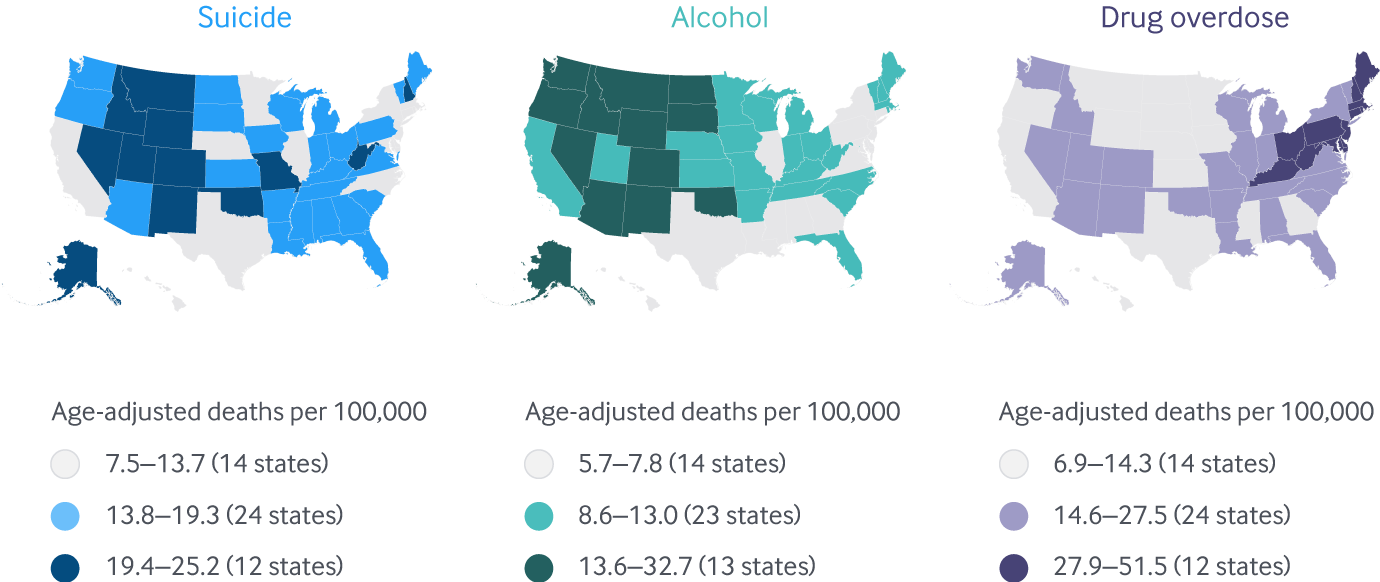

Deaths from suicide, alcohol, and drug overdose have all climbed over the past few decades and have been an important contributor to recent mortality trends.20These types of death differ significantly in terms of regional impact.

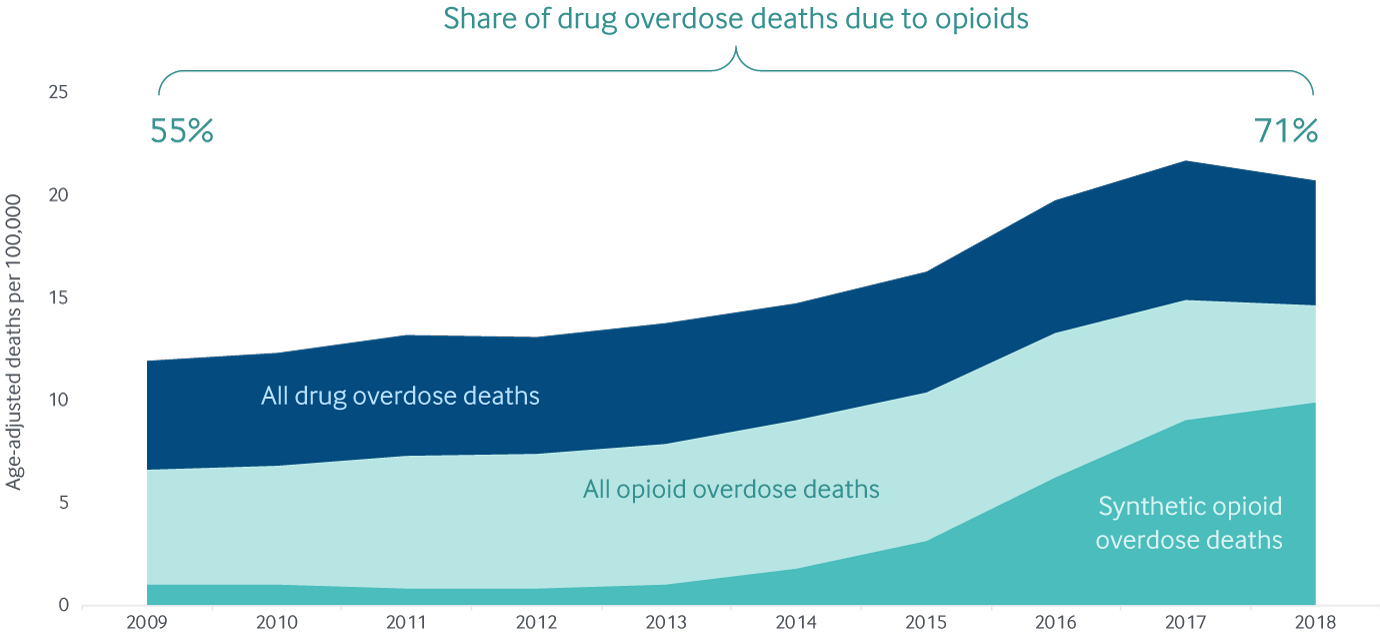

Opioids have been a critical driver, particularly since 2012, when the impact of synthetic opioids like fentanyl expanded. Since then, synthetic opioid overdoses have grown from 6 percent of all overdose deaths to nearly half. In 2018, the U.S. reported its first significant decline in drug overdose deaths in decades; however, the rate of synthetic opioid overdose deaths increased another 10 percent. Ten states and the District of Columbia attributed more than 20 deaths per 100,000 people to this cause. Unfortunately, preliminary estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also show that drug overdose deaths jumped again in 2019, despite recent federal support and state efforts (preliminary 2019 data not shown in Exhibit 8).21

Research indicates that higher local unemployment or economic shocks may be associated with increased overdose deaths from opioids or other drugs, as well as poor mental health.22 Experts have warned about potential consequences from COVID-19 on so-called deaths of despair, and recent reports indicate increases in overdose deaths in 2020.23 The 38 states that, along with the District of Columbia, have expanded their Medicaid programs are much better prepared to address a pandemic-related rise in substance use. Studies have found that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion is associated with improvement in access to mental health care,24 greater access to medication-assisted treatment,25 and fewer opioid-related overdose deaths and hospitalizations.26

Suicide and alcohol deaths rose modestly in 2018. Though drug overdoses dropped for the first time in decades, preliminary 2019 data shows that they have jumped back up

Note: Preliminary 2019 drug overdose data from the CDC is not included in this exhibit (see text).

Data: 2005–2018 National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), via CDC WONDER.

Share

Deaths from suicide, alcohol, and drug overdoses display significant regional variation

Note: District of Columbia not included in legend counts.

Data: 2018 National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), via CDC WONDER.

Share

Opioids contributed heavily to the overall rise in overdose deaths between 2009 and 2018, largely due to synthetic opioids

Note: Data categories are overlaid, not stacked/aggregated; synthetic opioid deaths are from synthetic opioids other than methadone.

Data: 2009–2018 National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), via CDC WONDER

Share

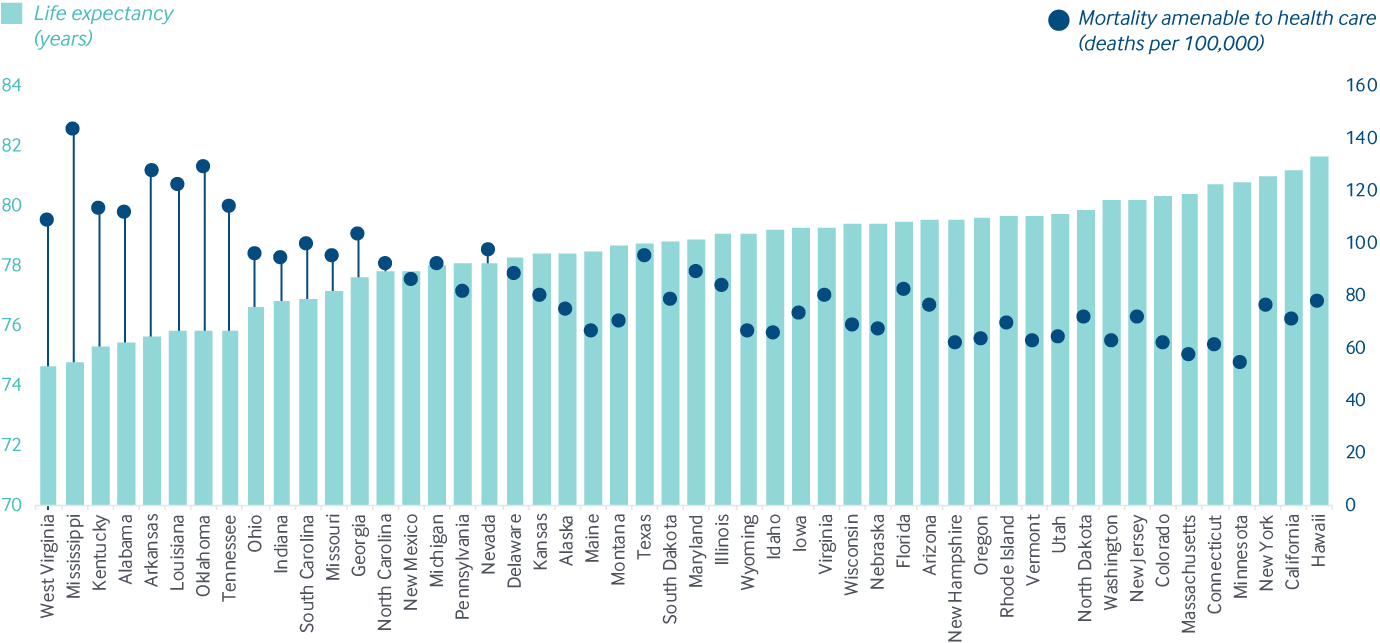

Premature deaths from treatable conditions

Americans can expect to live a shorter life today than they did in 2014.27 A number of factors contribute to this decline, including deaths from suicide, alcohol, and drug overdose, but another is premature deaths from health care–treatable conditions — also known as mortality amenable to health care. The Scorecard tracks deaths before age 75 from acute and chronic causes that are considered treatable when they are identified early and well managed; examples include appendicitis, certain cancers, heart disease, and diabetes, among others. Higher mortality rates in these categories point to deficiencies in the health system.

Between 2012–2013 and 2016–2017, these mortality rates either increased slightly or were unchanged in 37 states.28 Oklahoma, Arkansas, New Mexico, Kentucky, and Mississippi saw the biggest rise in premature deaths. States with the highest premature death rates also have lower life expectancies, and recent research linked life expectancy disparities to specific state policy choices.29

Black Americans, who have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic, are much more likely to die from some of these conditions, several of which are key risk factors for COVID-19.30 Significant racial disparities in mortality amenable to health care exist in nearly every state. The pandemic threatens to exacerbate these trends even further through the disruption of primary care and other critical health services. Early data suggest elevated mortality from non-COVID-19 causes.31

Premature deaths from treatable conditions are closely linked to the wide variation in state life expectancy

Data: Life Expectancy: United States Mortality Database, University of California, Berkeley; available at usa.mortality.org (data shown on 2020-05-11 12:22:03). Mortality Amenable to Health Care: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016 and 2017 National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), All-County Micro Data, Restricted Use Files

Share

In every state, Black people are more likely to die early from treatable conditions, 2016–17

Notes: Data for Black individuals not available for Idaho, Montana, Vermont, or Wyoming. States arranged in rank order based on Black mortality rates.

Data: CDC 2016 and 2017 National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), All-County Micro Data, Restricted Use Files

Share

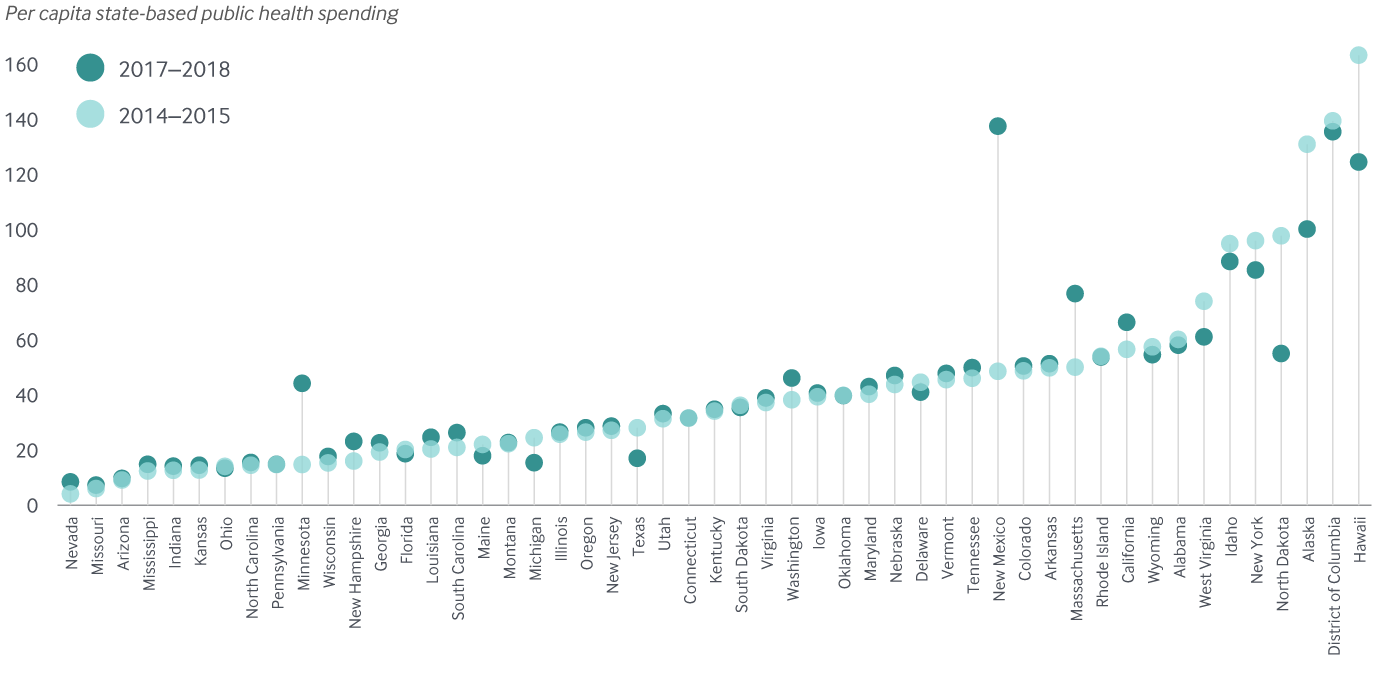

Public health investment.

States are navigating unprecedented public health threats from COVID-19, as well as economic disruptions that have shrunk the tax revenues used to fund critical health and social services. But historically, most states have made only modest investments in their public health systems.

Between 2014–2015 and 2017–2018, per capita public health spending was flat in most states, and increases were modest in the states where funding did rise.

Not only is public health funding low relative to other health care spending, but public health dollars are stretched thin. Competing for funding are various initiatives for emergency preparedness, disease prevention, promoting healthy behaviors, and, increasingly, fighting the opioid epidemic.32

Most states have seen modest changes in per capita public health spending in recent years

Notes: Estimates here include only state-based funding; federal public health funds are not included.

Data: 2017–2018 estimates: Trust for America’s Health, The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2019 (TFAH, Apr. 2019); 2014–2015 estimates: Trust for America’s Health, Investing in America’s Health: A State-by-State Look at Public Health Funding and Key Health Facts (TFAH, Apr. 2016).